I don’t play “real” chess tournaments all that often these days. The kind that last several days, maybe a week, with one or at most two games per day. It’s a bit tricky to fit into the rest of life, but I keep an eye on the calendar for opportunities. Because it really is a special experience to spend several days diving into oneself and just playing. There might be some socializing—there are almost always lots of old friends around—but for the most part I’m practically silent the whole time, playing my games and spending the time between rounds enjoying good food and reading a few books.

The result is rarely anything to write home about. I still play at a decent level, but it feels like the mistakes have become more dramatic and decisive compared to when I was younger. And if one is to believe what everyone says, the years do bring valuable experience—more patterns are stored, and one can draw from the memory of thousands of tournament games. But at the same time, the thoughts get slower each year, calculating variations becomes more sluggish, and the blunders seem to increase.

The last time I played for real was at the Reykjavík Open three years ago. We were a group of a dozen or so players from Uppsala SSS and had a real adventure—both on and off the board. Of course, we took a trip to the geysers and to Þingvellir, but the most enticing visit was to Selfoss, to see Bobby Fischer’s grave and the museum commemorating the 1972 match between Fischer and Boris Spassky. That match defined both Fischer as a player and Iceland as a chess nation, and its presence is still very much felt when one visits Iceland as a chess player.

The Reykjavík Open is one of the best open tournaments in the world. “Open” means anyone can register and everyone plays in the same class. It’s pretty cool, and if you’re lucky, you might get the chance to test your skills against a real star.

Two of the big names that year were the young Indians Gukesh and Praggnanandhaa. Both kept impressing, and news of their successes kept coming—yet they were only 16 and 17 years old! And when trying to figure out who I might be paired against in round one, it wasn’t out of the question that it could be one of them. That would have been so cool!

I ended up facing a very strong player in round one, though not one of those I had hoped for. Instead, it was an 18-year-old American I hadn’t heard of. His rating was over 2600, so he was clearly a star, and it was still an amazing challenge. His name was Hans Moke Niemann, and while he wasn’t very well known at the time, that would soon change—just a few months later he would win a beautiful game against Magnus Carlsen, but that’s a different story.

The top five boards were placed on a small podium, and I was to play there (Gukesh was at the board next to mine!). Playing black against the tournament’s third-highest-ranked player wasn’t likely to yield much beyond a cool experience, but that’s not so bad. So I sat down and got started.

Hans Moke Niemann – Carl Fredrik Johansson, Reykjavík Open 2022

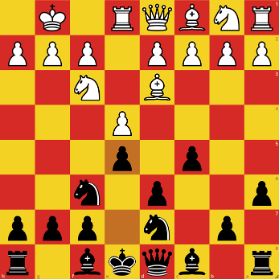

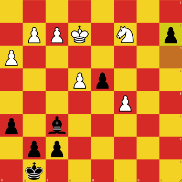

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.Bb5+ Nd7 4.O-O a6 5.Bd3 Nf6 6.Re1 e5?

Already this early, I go wrong. Advancing the e-pawn two squares here was much worse than I realized at the time. And I really found that out after the game. In the post-game analysis, Hans told me he had looked through a few of my games before the round. I was a bit surprised just by that information—since it was the first round of the tournament, you found out who your opponent was only shortly before the game started, so there weren’t many minutes to prepare. But what he told me made me understand much more clearly the gap between a regular patzer like me and a world-class player.

He had noticed that in similar positions, I had played the move e7–e5 in two games—and apparently both times I had played it almost instantly. His analysis, then, was that this move was “obvious” to me, and since he understood that it would lead to positions where White stands excellently and Black is stuck in hopeless, dull setups, he chose this opening—despite normally playing something entirely different.

7.c3 Be7 8.a4 Nf8 9.Bf1 Ng6 10.d4 Bg4

11.dxc5!

This move defines the central pawn structure, and it’s immediately clear that I would prefer to have either a pawn on e5 or on c5—in this case, having both means my pieces lack too many useful squares. I had dreams about 11.d5—with a closed center I felt I might get reasonable chances for play on the kingside—but that idea likely never even crossed his radar.

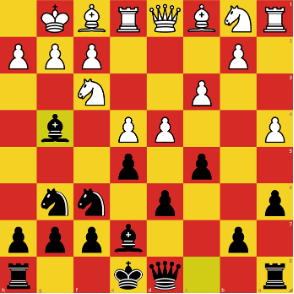

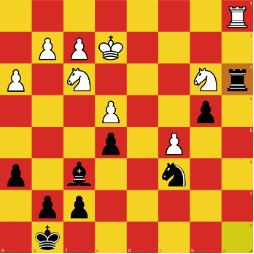

11… dxc5 12.Qxd8+!

A quick comparison of our pieces brings nothing but bad news for me. My dark-squared bishop in particular is quite miserable. Even in my wildest dreams, I can’t find a decent square for it. When a much stronger player makes a move like this against you, you’re left feeling like you understand absolutely nothing at all.

12… Rxd8 13.Nbd2 O-O 14.h3 Bd7

I try to hold on to the few pieces that are still functioning somewhat reasonably.

15.Nc4 Bc6!

I was pleased with this move. White has to keep the e-pawn defended as long as I threaten it, and the tactic works.

16.Bg5

If 16.Nxe5 Nxe5 17.Nxe5 Bxe4, and suddenly my pieces are far livelier than they deserve to be.

16… h6 17.Bxf6

These kinds of exchanges impress me. One part of my brain thinks, “fewer pieces on the board = closer to a draw.” But the other, wiser part realizes that he’s simply exchanging pieces so that the remaining white ones are better than the black ones.

17… Bxf6 18.Na5 Ne7

Here I had calculated quite carefully the possibility that Niemann would play 19.b4, which looks natural. It gives White more space on the queenside and looks pretty scary. But my pieces were actually well-prepared to face it—even if I wasn’t entirely confident it would hold.

19.b4?

But the natural move was rushed—there was no need to hurry. I had prepared the coming sequence well, and I believe there’s only one path that keeps the game afloat.

19… cxb4 20.cxb4 b5! 21.Rac1 Rc8 22.Rc5 Be8!

I was very pleased with this move during the game, even though the engine now says 22…bxa4 was slightly better. In any case, Black has surprisingly gotten the pieces more in order over the last few moves. Since I can tactically hold both b5 and e5, White’s plan has faltered a bit—and if you look closely, his pieces aren’t that wonderfully placed anymore either.

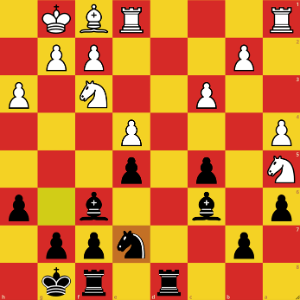

23.axb5 Rxc5 24.bxc5 axb5 25.Bxb5 axb5 26.Rb1 Rb8

Somewhere around here, for the first time in the game, I could breathe a bit more easily. I knew I had weathered the worst storm and that the position was fairly equal.

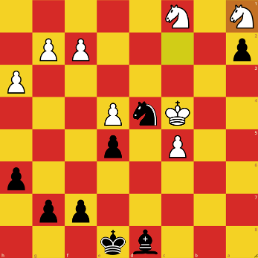

27.Kf1 b4 28.Ke2 Ra8!

The start of a slightly tricky plan.

29.Ra1 Nc6 30.Nb3 Ra3!

I was really fond of this move, and in the post-game analysis, Hans said he had either missed it or seriously underestimated it.

31.Rxa3 bxa3

Now my passed pawn is certainly no less dangerous than his.

32.Ne1 a2?

But just one move later, I gave the game back. Time was getting short—there was a time control at move 40—and the move I tried calculating was 32.Nd4+. It’s the kind of forcing move you should start analyzing first, but I couldn’t make anything work. So I thought: I can always play Nd4 on the next move, but the a-pawn needs to move anyway—and since I didn’t think it looked more vulnerable on a2 than a3, this move felt like the only reasonable option.

But unfortunately, I chose wrong. 32… Nd4+! is so much better than I had realized. After 33.Nxd4 exd4 34.Nc2 a2 (diagram), the knight is tied down to defending a1. White might be able to hold, but it’s not easy. For example: 35.g3 Be7 36.c6 Bd8 37.Kd3 Ba5 38.c7 Bxc7 39.Kxd4 Ba5+, and Black wins. So close, yet so far away.

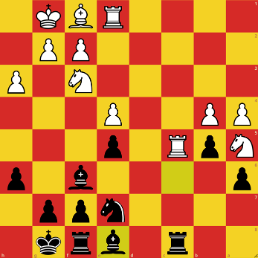

33.Nc2! Bd8?

Not objectively terrible, but it shows I have no real plan. 33…Nd4+ could have still been played, although it’s not as powerful now that White’s knights are in position. 34.Nxd4 exd4 35.f4 and the game feels roughly equal.

34.Kd3 Kf8 35.Kc4 Ke8

Hans complimented this move after the game, but the variation he thought I had calculated—which required the king to go precisely here—was something I hadn’t thought about at all.

36.Nc1 Nd4 37.Na1

37… Kd7?

37… Ne6! was the last chance to save the game, with the idea of shifting play to the kingside via f4 when White tries to push the c-pawn. But I hadn’t seen the idea at all. I think it’s mentally difficult to realize that I should suddenly switch sides after the last 20 moves have been exclusively on the queenside. After 38.Nxa2 Nf4 39.Nc4 Nxg2 40.Nd3 g5, it’s not at all clear that Black is worse.

38.Nxa2

Now the passed pawn is gone, and I have nothing left. The rest of the moves are just a dreary road to the inevitable conclusion.

38… Ba5 39.Nc3 Nxb3 40.Kxb3 g6 41.Nd3 h5 42.Kc4 f5 43.f3 h4 44.Nf2 Ke6 45.Kb5 Bd8 46.Kc6 f4 47.Kb7 g5 48.Nc2 resign

After a long game, it’s not uncommon for the players to head to an adjacent room (the “analysis room”) to go through the game together—discussing their thinking and seeing if there was anything smarter they could have done. But when an older man (me), nowhere near elite level, has played against a young superstar, it’s not exactly expected. I honestly thought Hans might just move on to hang out with his peers or prepare for the next round. But when I humbly asked if he’d be willing to go through the game together, he replied, “Gladly,” and we brought a board to the bar in the basement of Harpa (a very cool venue), grabbed a beer each, and sat for an hour talking about the game.

Johan Sigeman joined us, and in addition to analyzing the game, we had the chance to chat with a true chess professional about all sorts of things. Hans told us he felt like a nomad, with roots in Germany, Denmark and Hawaii, spending nearly the entire year on the road, traveling from tournament to tournament and just playing. It didn’t bring in big money, but grandmasters often don’t pay for lodging or meals during tournaments, and it was clearly a lifestyle that worked for him. With low expenses, even small prize winnings could significantly raise his standard of living.

Just a few months later, the whole world knew who he was. And despite how poorly he’s been treated by chess.com and many others, he has continued climbing the rankings and is now ranked among the world’s top 20. A nomadic chess life clearly suits him.

In a few weeks, it’s time for another chess event. In Stavanger, Kjell Madland has for many years organized Norway Chess, one of the few events that reliably attracts the world’s top players each year. It’s fair to say that Magnus Carlsen’s participation is a major draw, but it’s a beautifully organized tournament and they go all out to make both players and spectators feel welcome.

Last year, Norway Chess was played in both an open and a women’s group, with everything equal between the two—including prize funds. This rightly garnered attention, and the same format is planned again this year. In the men’s group, we have Magnus Carlsen (ranked no. 1), Gukesh (World Champion), Hikaru Nakamura (2), Arjun Erigaisi (4), Fabiano Caruana (5), and Wei Yi (8). Among the women: Ju Wenjun (World Champion), Lei Tingjie (4), Humpy Koneru (6), Anna Muzychuk (8), Vaishali (16), and the Spanish/Iranian outsider Sarasadat Khademalsharieh.

Six players in each group, playing double round-robins—something truly special to follow.

Alongside Norway Chess this year, there will be an open tournament, which I’ve registered for. Aside from giving myself a proper chess week, it will be great fun to watch the superstars up close. There will be a few grandmasters in the open tournament too, but their playing strength is nowhere near the galactic level of the top-tier names. Maybe I’ll get a chance to play one of them—how fun that would be.

My tournament is nine rounds over seven days. Even with a tight schedule, there should still be some time to explore what Stavanger has to offer. Or maybe just some quiet days together with a few unread books. One that’s definitely coming with me is Susan Polgar’s latest, Rebel Queen, with the irresistible subtitle The Cold War, Misogyny and the Making of a Grandmaster. She has so many stories to tell—and if she manages to maintain some distance to herself in the book, it promises to be a very interesting read.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.